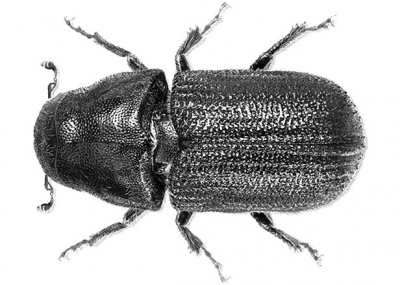

| Mountain Pine Beetle Story January 29, 2021  The Mountain Pine Beetle epidemic was devastating to the Black Hills, especially around the Custer area. It killed hundreds of thousands of trees. Below is information from two different articles written about the Mountain Pine Beetle. The first one was written in 2012 and gives some good historical data. The second one was written in 2016/2017 and has more updated information about the current status of the Mountain Pine Beetle infestation. Early Battles Against the Mountain Pine Beetle | Finding Zippy: A Tale of an Elf Gone Astray Written by Adrianna Burgess December 10, 2024  Plan for the 101st Annual Gold Discovery Days Celebration July 16, 2024 National Trails Day Written by Darian Block May 31, 2024  BRIDGES OF CUSTER COUNTY March 27, 2024 Groundhog Day! Written by Andrea Spaans February 1, 2024 |

|

||||

|

|

||||